--Lewis Carroll, Alice In Wonderland

And so, on to the final chapter of the story. Well, I am hoping this will be the final chapter.

BEFORE

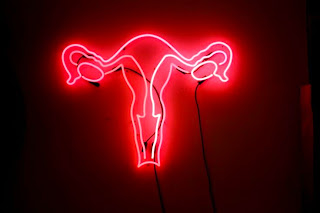

My pre-surgery appointment was

scheduled for Wednesday, May 27 at 10 AM. Kia Prescott, Dr. Muto’s Physician

Assistant, went over the particulars: this would be a complete hysterectomy,

removing the uterus, fallopian tubes and ovaries. (By now I had given up on my

crusade to retain my ovaries. Dr. Muto had reasoned that at this point in my

life, my ovaries excrete nothing.

Zilch. Nada. Zero. “If you were 39 years old, there would be a reason to debate

this. But not at 63.”) Kia’s main focus was the aftermath of the operation.

“You’re going to be tired for at least 6 weeks. Listen to what your body is

telling you. Don’t lift anything heavy. Rest. Take naps. You will not be able

to run around because you will hit the wall and come to a crashing halt. And

when I say hit the wall, I mean

you’ll have no reserves.” She delivered all of this forthrightly and

cheerfully, patiently enduring my repeated assertions about being as strong as

an ox. I bounce back from everything in record time, I insisted. “You’ll see,

you’re going to be a hot mess,” she smiled sweetly.

This was followed by a brief

conversation with the anesthesiologist. I repeated what I always say when meeting

an anesthesiologist, “No ketamine.” The

doctor assured me that ketamine was no longer used on human beings. (“It’s only

been used on horses for years!”) But on the subject of ketamine, my motto is Better Safe Than Sorry. I’d experienced

it 30 years ago when New York Hospital reset my broken nose, and life became an endless screening of the Sorcerer’s

Apprentice for the next several months.

|

| Ketamine's aftermath |

With the anesthesiologist’s guarantee that ketamine was off the table, and armed with instructions to call and confirm my surgery appointment for noon the next day, we went to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts to spend the afternoon.

|

| John Singer Sargent paints sparkling white linen like no one else in this world. |

|

| zzzzZZZZZZZZ |

Prepping for surgery is a little

like watching your life pass before your eyes. Only in this case, it’s not your

life's story crossing your field of vision, but an entire surgical team that comes

through, introducing itself one by one, asking if you know why you’re here, what

kind of surgery you’re expecting to have done, and if any of your teeth are

loose. (Again with the teeth?!) One member

of the team was a standout—Dominick, the anesthesiologist nurse. I wish I’d

asked his last name, because he was wonderful. Dominick took the time to

explain every move that would take place once I was in the operating room,

walking me through everything I would observe before falling asleep. This was

obviously done for the benefit of nervous patients, and it was the absolutely

perfect touch. The explanation included everything from how I would be moved from the

gurney to the operating table, to the moment when he would cease speaking to me

and turn to the surgical team to give them a status update.

The last thing I

recall before the lights went out was Dominick patting my shoulder, assuring me

that he would take good care of me, and promising me that I wouldn’t wake up

during the surgery. It hadn’t even occurred to me that this could happen. Hmmm, now that's a |

| Now that's a party hat. |

AFTER

I awoke to Peter’s and my brother,

Steve’s smiling faces. The recovery room was bustling beyond my pleasant haze

of drugs. I was offered vanilla pudding in a tiny dixie cup. I ate it with

drug-sodden gusto and was reduced to a gaga bleating of Oliver Twist’s, May I have some more, please? For the

time being, the usual zzZZZZZ had been reduced to hmmmmmm.

Steve, had come up from New York to

be with me. Over the years, Steve and I have made it a practice to sit with and

for each other during surgeries. Steve kept me company while Peter underwent back

surgeries. I sat with him while his wife, Susan, had surgery. We’ve never

discussed why or how this tradition came to be. As children, Steve and I fought endlessly. (I used to say that my

brother never spoke a civil word to me until I went off to college.) In a quiet

moment my mother took me aside and told me we shouldn’t fight because someday

she and my father would be gone, and Steve and I would have only each other.

|

| Steve Doloff |

Somehow I got dressed. Peter must have made that happen. I was still so gaga

that I could easily have pulled my panties on over my yoga pants and thought I was ready to go dancing. I was poured into a wheelchair and rolled out of the hospital.

Although our hotel was two blocks from the hospital, Peter brought the car

around to pick me up. Steve stood beside me holding my hand, while I sat in the

wheelchair, blissed out, dreamy and secure in my brother’s company and care.

The hospital sent me home with scrip’s for big honkin’ bottles of 600 mg Ibuprofen and OxyCodone. The amount and magnitude of the medications seemed vastly out of line with the minor discomfort I was experiencing. True, urinating did sting for the next day or so, and I did feel like my bladder had been neatly folded in quarters, and then unfolded and refolded a few more times. (Having your hooha clamped wide open for almost two hours and your organs moved around like chops on a grill will have that effect.) But over-the-counter Advil would have done the trick.

The hospital sent me home with scrip’s for big honkin’ bottles of 600 mg Ibuprofen and OxyCodone. The amount and magnitude of the medications seemed vastly out of line with the minor discomfort I was experiencing. True, urinating did sting for the next day or so, and I did feel like my bladder had been neatly folded in quarters, and then unfolded and refolded a few more times. (Having your hooha clamped wide open for almost two hours and your organs moved around like chops on a grill will have that effect.) But over-the-counter Advil would have done the trick.

AFTER AFTER

Life is an elaborate and endless to-do list, and I plan my own life with bullet-points, indented sections and

subsections. But the list was put aside for the next

several weeks. I slept a great deal, I ate a very little, and somehow the time

passed hazily, pleasantly and uneventfully. The mild soreness passed, the fatigue that

Kia predicted did overcome me in many small ways over many late spring

afternoons. Amazingly, I was smart enough not to over-exert myself, so I never

did live out her prediction of becoming a hot mess. The lethargy was so pleasant, in fact, that I wondered if I would ever get beyond it. I missed the habitual zzzzzzzzz in my head, and asked myself, What happens if it doesn't come back, and I'm stuck in hmmmmm for the rest of my life? I needn't have worried. It came back with a vengeance (albeit, in fits and starts), and I am happily making and checking off long to-do lists again.

The pathology report was a howling success. The cancer was confirmed to be early, slow growing, and making only minor inroads into the muscle. Even better, the genetic testing showed no

inherent predisposition to the cancer. As Dr. Muto termed it, This was just a lightning strike.

And so we move forward. I dodged a bullet this time, and am immensely

grateful and relieved to have done so. But my blithe certainty of many

healthy years ahead is rightfully shaken. And the fragility of life and its

tender connections to beloved husbands, brothers, friends and memories are spread out before me plainly, just as they were when my mother and father died.